Translation

How the lie of Catalan independence has come to triumph in Valencia

March 2025

Cómo ha llegado a triunfar la mentira del independentismo catalán en Valencia

The author of the original Spanish text is Dr Josefa Villanueva Espinosa

Translated by Google Translate

In Valencia, we have been hearing about the Catalanness of the Valencian language for more than a hundred years, when in previous centuries no one would have thought of making such a statement or raising such a debate. The truth is that it was Catalan nationalism that brought about this controversy at the beginning of the 20th century (1902), hence the issue of the Catalanness of Valenciano is a purely political issue, which has been deliberately disguised as a scientific debate in order to mislead people and above all to rob the Valencian people of their right to have their own language.

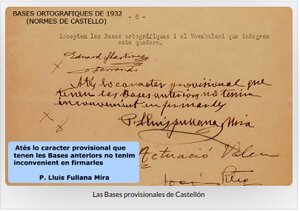

Therefore, in order to unmask the linguistic conflict created in Valencia, it is necessary to go back to its political roots and examine its first victory in Valencia, which was the signing of the document called „the Bases of Castellón“ on 21 December 1932. The year is no coincidence, and contrary to what that date implied, the event went unnoticed by the Valencian population as it was hardly publicised and consisted of the signing of a particular document in which a very small group of Valencians took part, who of course acted in collusion with the Catalan nationalists of the Regionalist League and Esquerra Republicana de Cataluña. Contrary to what the pancatalanists repeatedly proclaim, in that document it was not written anywhere that Valenciano was Catalan or a modality of Catalan. This apparent contradiction can be explained by the fact that the decision was taken de facto to write Valenciano by adopting the Catalan rules of the Institute of Catalan Studies, recently defined (November 1932), but without declaring it, that is to say, without reasoning it as it would have been necessary to do, for pure coherence; which constituted an incongruence as well as a disloyalty.

The historical context says it all: the Catalans had just obtained the first statute of autonomy (09/09/1932) and since the beginning of the 20th century there had been an orchestrated campaign in Valencia from Barcelona to attract Valencians eager to follow the same path as the Catalan nationalists: to join nationalism, but not Valencian nationalism, but Catalan nationalism, politically very active in the Spanish Parliament. Catalonia was copying a phenomenon that already existed in other parts of Europe, which consisted of making language and culture recurrent pretexts to try to change borders, even at the cost of provoking wars, such as the First and Second World Wars. Let us say that nationalism tends by nature to be expansionist, hence the Catalan nationalists' interest in extending Catalan territory to include the entire Valencian region as well as the Balearic Islands, even setting their sights on French Catalonia („le Roussillon“).

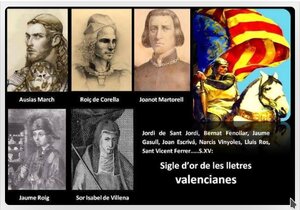

However, the Catalanists encountered a significant difficulty: the coveted Valencian territory had a recognized language since the 14th century, thanks to its classics (the Golden Age with Joanot Martorell, Jordí de Sant Jordí, Ausias March, Jaume Roig, Joan Rois de Corella, Sor Isabel de Villena), while the Catalans did not have a true language in the strictest sense, but rather a dialectal complex. Or to put it another way, the Catalan language did not exist as such because it had no fixed, written norms; so much so that educated Catalans wrote in Provençal, proof that the popular dialects that prevailed in those counties at the time held no prestige or interest for them. And here we must reflect: if Catalan was not properly a language, how could it have given rise to a language like Valencian, which established its own model and its own norms? Or, to put it graphically, how could a person win the 100-meter butterfly race when they are still in the initial stages of learning to swim? Which means it's absolutely ridiculous to claim now that the Valencian Golden Age developed in the Catalan language, when the Catalans of that time neither experienced it nor expressed it that way. You won't find a single historical document in which 15th-century Catalans claim authorship of Valencian literature of that century. So why would they claim it in the 20th century? Making comparisons would be like claiming that the Golden Age of the Spanish language developed in the half-conquered America and not in Spain, where, paradoxically, there would have been no awareness of having a Golden Age. As we can see, the pan-Catalanist thesis doesn't hold up in any way. The emergence of a Golden Age is inextricably linked to a particular social context, such as that of 15th-century Valencia, prosperous and experiencing full material and intellectual expansion, with a new institutional system and, above all, the awareness of being an independent kingdom within the Crown of Aragon. Valencia was only linked to the Catalan counties by the person of the king. The same occurred in 16th and 17th-century Spain; it was undergoing a great transformation that led to the inauguration of a new era for the world, the Modern Age, where Spanish thinkers were at the center of great philosophical debates (various authors such as Cervantes, etc.), legal debates (the School of Salamanca and the invention of International Law, etc.), and religious debates (for example, Ignatius of Loyola and the creation of the Society of Jesus, etc.). And another thing: how could the Catalan counties have been aware of having a single language of their own when not even that awareness of territorial unity existed? When James I conquered Valencia (1238), the Treaty of Corbeil (1258), which brought peace between France and the Crown of Aragon, had not yet been signed. James I ceded the territories north of the Pyrenees (except for the Lordship of Montpellier) in exchange for obtaining ownership of the Catalan counties south of the Pyrenees. On paper, by virtue of historical rights, these Catalan counties still belonged to the King of France (a Hispanic March dating back to the reconquest by the Franks). Therefore, Catalonia was not at all the Catalonia we see today—a cohesive territory—but rather a set of counties, practically independent of one another, with internal rivalries hardly conducive to moments of splendor, let alone cultural ones. In contrast, the Kingdom of Valencia was already aware of territorial and cultural unity, having been a Moorish kingdom since at least 1011.

Now, by the 20th century, it's true that the Valencian language was experiencing a certain orthographic anarchy, because throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, the language had followed its natural evolution—as was normal—but without a corresponding transcription. In other words, the problem of the Valencian Golden Age was that it failed to create a Valencian dictionary in the academic sense, as had happened with the Spanish Golden Age (that of Antonio de Nebrija: Latin/Spanish 1492; that of Sebastián de Covarrubias 1611). In the Valencian case, these dictionaries arrived later, around the 18th century (Carlos Ros, José Escrig Martínez, or Josep Nebot Pérez), which created a significant gap between the written and spoken language. Pan-Catalanists exploit this circumstance to accuse and vilify the Valencian nobility and elite who preferred to speak and cultivate Castilian during those centuries. It's true that the nobility in general lost interest in their own language because they were more interested in speaking the king's language, when social advancement evidently always pushed them toward the Court. This happened in every country, and besides, human nature is what it is; elites always want to rub shoulders with elites; they take their codes from the wealthiest and never from the common people. But we cannot accept that this is why people now want to believe that Valencian was an abandoned language, because that is radically false. Not only did the people continue to speak it, but also a bourgeoisie who also wrote it. But the Pan-Catalanists have preferred to talk about abandonment to convince Valencian society that they are the true defenders of the Valencian language and culture. In other words, they are the ones who have captured the true essence of Valencian identity, a ruse they use to send a subliminal and destructive message: none other than that anyone who compromises with Castilian culture—as the nobility did—is a traitor to the Valencian people. But they are the ones who truly betray the essence of Valencia, by adulterating it by Catalanizing it. And if the nobility neglected the Valencian language, there still existed a bourgeoisie that did take care to write and appreciate its own language.

Thanks to the dedicated work of Brother Josep Alminyana Vallés, we know that Fray Josep Rodríguez (1630-1703) dedicated 20 years of his life to compiling the names of unjustly forgotten Valencian authors who, over the centuries, wrote or reclaimed their language. These names are compiled in his work Biblioteca Valentina. But there's more, because in addition to this list of cultured authors, we must add a whole cast of authors who wrote directly for the people; a people who at that time were largely illiterate. They addressed them through loose sheets, republican newspapers (El Mole, La Traca, etc.), and also books of fallas and sainetes (Josep Bernat i Baldoví). They preferred to use Castilian orthography—easier to understand—to transcribe this very vibrant Valencian language. Here, the pan-Catalanists' response has been to claim that these popular authors were uncultured. A blatant lie, because there were highly respected people among them, who, precisely because of their republican ideology, believed that the people's access to information and culture should be facilitated, but they considered the script of Old Valenciano to be an obstacle. In short, the pan-Catalanists have exploited the ignorance of these people like no one else, whom they claim to want to save and restore their culture.

For their part, the Catalan nationalists quickly understood that unifying the territories required unifying the culture as well as the language. Converting the Valencian language into the Catalan language required a gradual process of orthographic, grammatical, and even lexical convergence (because there are very different words that express the same thing. For example: in Catalan: „sortida.“ In Valenciano: „eixida“). To carry out this metamorphosis, they first resorted to an ancient term that referred to the common root of both languages: the designation „Limousin language,“ which appears in some ancient texts - and not so ancient (written by 19th-century Catalan authors: Joaquim Rubió i Ors; Manuel Milà i Fontanals; Francisco Piferrer Montells, etc.) - to refer to all the dialects from Catalonia to Valencia, including the Balearic Islands. This served as a way for Catalanists to claim that this was an „error“ on the part of the ancient authors and that wherever it said „Limousin language“ or „Llemosí“, it should be understood that it was referring to the Catalan language. To this end, the First International Congress of the Catalan Language was held in Barcelona in 1906, which served to present to invited specialists from other countries what the Catalanists wanted to be considered the territorial domain of the Catalan „language“. To this end, the use of the words „Valenciano“ and „Mallorcan“ to refer to the respective languages was prohibited. It was referred to as a „common language“. The following year, 1907, they rushed to create the Institute of Catalan Studies (IEC), where Pompeu Fabra was almost single-handedly tasked with defining an orthography as far removed from Castilian as possible (orthographic dictionary in 1913), as well as a grammar (grammatical dictionary in 1918), and a lexicon (lexical dictionary in 1932). This means that Catalan is a laboratory language, created ex professo to structure the political project; unlike Valenciano, which was created by a literary elite, a witness to the flourishing of Valencian culture. It should be noted that Pompeu Fabra was not even a specialist in linguistics, but was an industrial engineer by profession, a linguist, and above all, deeply involved in politics.

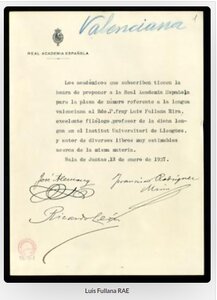

There is no doubt that this gentleman has been overrated. He did not become a representative of the Catalan language in 1926 (by virtue of the Royal Decree of November 26, 1926, which appointed several representatives of the regional languages) before the Royal Spanish Academy of Language, while Father Fullana was granted the distinction of representative of the Valencian language. And although a university in Catalonia has been named after him (Pompeu Fabra University), he never received public recognition from any foreign expert as a linguist. The separatists always erase from the past everything that bothers them, but there remains evidence of the significant opposition that Pompeu Fabra's work aroused in Barcelona among contemporary literary figures of great social prestige who considered his new spelling rules to be utter nonsense. We are talking about Apeles Mestres and Oños; Narcís Oller and Moragas; Ángel Guimerá and Jorge; Francesc Matheu i Fornells, among others, founded an Academy of the Catalan Language in 1915, where they published a set of Orthographic Rules, which were opposed to the Fabrian rules (Normes Ortogràfiques de 1913). Most of them already belonged to the Royal Academy of Letters of Barcelona, such as its president, Josep Balari i Jovany, a philologist, Hellenist, historian, shorthand writer, and a great expert on the history of Catalonia, who had written a work entitled Historical Origins of Catalonia. There was also Alfons Par Tusquets, Francesc Carreras y Candi, or Ramón Miquel y Planas, who called him a „linguistic dictator“, or Jaume Collell y Bancells, who reproached him for his stupid obsession with distancing Catalan spellings as far from Castilian as possible, even introducing ridiculous changes such as changing the consonants „mb“ to „nv“, affecting words like „cambio“, artificially Catalanized by writing „canvi“ instead of „cambi“; when its natural development from Latin was „cambium“. In this regard, Josep Pin y Soler even mocked that any day he would see the transformation of Francesc Cambó's name into Canvó. Evidently, Fabra was supported by an entire wealthy industrial bourgeoisie that held political control of the region (a Regionalist League party) first through the Mancomunitat (Mancomunitat) and then through the Statute of Autonomy.

It's important to keep in mind that Catalan nationalists had begun to gain political strength in the national parliament at the beginning of the 20th century. They were divided into several political parties (right-wing: the Regionalist League; left-wing: Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya), which, however, operated in a coordinated manner in Madrid, always keeping in mind that the enemy to be defeated was the central government (which is what they have continued to do to this day).

When it suited them, they supported Primo de Rivera's dictatorship, and when it didn't, they supported the Second Republic in exchange for that future republic granting them a statute of autonomy (see the Pact of San Sebastián - 17/08/1930 -, a pure blackmail, something that inevitably recalls what we are now experiencing). The key point of the negotiation was transferred to the Constitution of 1931[1], because in its article 11, it was admitted that bordering territories (perhaps a province but not a region in its entirety) with historical or cultural affinities could federate. The prohibition of regional federations in Article 13 was of little use, as Catalan nationalists already had their hopes pinned on being able to repeal Article 13 in the future. Therefore, the Catalan nationalists were already acting in line with that objective: a future federation of the Valencia region with Catalonia and the same with the Balearic Islands. To achieve this, they had to prepare their minds with a narrative tailored to their needs. The Catalan nationalists had in their favor not only the social prestige granted to them by their economic and financial triumphs (the strength of the textile industry, benefiting from the tariffs adopted both to protect Catalan manufacturers from formidable English competition and to protect Castilian wheat producers from the low prices of foreign competition), but also a dominant position in the publishing world. See Espasa (1860), the parent company of Spanish publishing capitalism, which later gave rise to Editorial Salvat (1869) [then in 1925 Espasa merged with Madrid's Calpe (1918)]. Since then, the Catalan publishing industry has been unstoppable; see the paradigmatic case of Planeta (1949). Therefore there is no doubt that it was (and continues to be) a factor that helped to complement with ease and success the action carried out in the field of education, where several associations of the type „Nostra Parla“ (1916), Agrupació Nacionalista Escolar (1919), Acció Cultural Valenciana (1930), Agrupació Valencianista Escolar (1931), Centre d´Actuació Valencianista (1931) or Associació Protectora de l´Ensenyança (1934-1938) had already been set up., that is to say the equivalent of what we have today with Escola Vaís Valencià,…

At first, they encountered considerable resistance to establishing themselves in Valencia, but their effort, always carried out with great care, eventually yielded sufficient results to achieve relative success for two main reasons. First, because the establishment of the Second Republic offered a hopeful territorial framework for the pan-Catalanists; let's say, it gave them a platform by accepting the autonomous regions; and second, because the Catalanists had spent many years trying to plant the seed of the supposed „Catalan fraternity,“ whether of the „common language“ and the belief that a language is a nation and that only a „Catalan national“ union could bring success to Valencians, who admired the achievements of „Catalan Solidarity“ (1906 elections) or the Catalan Commonwealth (1914-1925), and above all, the Statute of Autonomy (1932); successes that heralded new political horizons. Let's say they presented themselves as the future, in the face of a Spain in decline after the disaster of 1898. They deployed a veritable social engineering operation, which they knew would only bear fruit in the long term, because it was a matter of focusing their recruitment efforts on Valencian youth. Of course, they quickly encouraged the creation of various political parties (Joventut Regionalista Valenciana in 1907, Joventut Valencianista in 1908, Joventut Nacionalista Republicana in 1915, Joventut Nacionalista Obrera in 1921) as well as newspapers (El Camí, Avant, Acció Valenciana, Poble Valencià, and La Correspondencia de Valencia), while also striving to penetrate as many and as many of the best educational centers as possible, in order to train this future elite and make them literally eager to link their political future to that of Catalonia (according to the Jesuit system: select the best, so that those best would guide the masses). Let's say that the typical strategy of the pan-Catalanists has been based on a discourse constructed on two main axes: on the one hand, practicing the discourse of ambiguity to gradually mix Valencian and Catalan (using expressions like common language, our language), until the concept of Valencian is diluted within Catalan. And, on the other hand, fostering hatred toward Spain, toward everything „Castilian“ or Spanish, legitimizing and leading a revolt against the supposed historical oppression of the Castilians.

And this is no exaggeration; one need only read Enric Prat de la Riba's book to see that the ideologue of Catalan nationalism openly preached a rejection of Spain, lamenting that: „The Catalan ésser (the essence of Catalonia) was still embedded like coral reefs in the Castilian ésser (the essence of Castilian)“[2]. It therefore became necessary to foster this feeling of resentment by associating, for Catalans, the date of the end of the War of the Spanish Succession—1714—with a humiliation of Catalonia before Spain, and for Valencians, the date of 1707 with the humiliation of Valencia. The feeling of hatred and revenge at the same time, in sufficient doses, should act as a catalyst for this change of mentality, even provoking the desire to change nationality. Let us say that the nationalists' litany of victimhood is now proverbial. But this is how the psychological boundary between Spain and those imagined „Catalan countries“ was quietly and deeply dug. And it was with these ideas in mind that 35 people (the number of signatures recorded on the document, not the 60 or even 70 they claim now) signed the „Castellón Bases“.

That document, always brandished by pan-Catalanists, is never shown. Why? Because it is characterized by its confusion, ambiguity, spelling mistakes, lack of a letterhead, and lack of academic authority of either personal or institutional reference. It is the furthest thing from a sound document, both linguistically and academically, legally, and institutionally. However, the same pan-Catalanists have dedicated themselves to sacralizing it, calling it „scientific“, „historical“ and other such praises. So it should come as no surprise that once an openly pan-Catalanist government (the Botánic Government) came to power in the Valencian Generalitat, it rushed to shield these „rules“ by declaring them „Assets of Intangible Cultural Interest“ (Decree No. 189/2016 of 16/12/2016). It's also part of the story that Catalan nationalists have spent a century training a legion of so-called specialists or experts dedicated to attesting to the scientific merits of pan-Catalanist theses, with the logical aim of countering criticism and avoiding serious analysis. Once again, the publishing world has been key, as has the policy of creating ad hoc prizes and, of course, showering all the entities dedicated to spreading pro-Catalanist ideas with a huge amount of money.

After inventing Catalan linguistic unity to justify Valencian as a dialect of Catalan, the next phase was to make people believe that Valenciano was simply Catalan. The ruse prepared consisted of claiming that Valenciano is the name of the Catalan language in Valencia. At the same time, linguistic unity was supposed to legitimize a Catalan territorial unity that had already existed in the past (a lie: the Crown of Aragon was not the „Kingdom“ of Catalonia, and its territories in the Mediterranean were not Catalan colonies). During the Second Republic, they spoke of creating „Great Catalonia“ (in the image of „Great Britain“). Later, with more caution, they preferred to speak of „Catalan Countries“ and this plan began to take shape in 1932, when the „Bases of Castellón“ were signed, which promptly renamed the „norms of Castellón“. This was an initial linguistic rapprochement that was to foreshadow the future political federation of Valencia with Catalonia. Well, look how quickly things went: as soon as the Catalan statute was voted on, on September 9, 1932, Pompeu Fabra published the last piece he was missing, his lexical dictionary in November 1932 (the formal moment in which the process of standardizing Catalan could be considered complete), having helped long before in the preparation of the document of the „Bases de Castellón“, which was signed the following month, on December 21 of the same year (1932). And the greatest difficulty was getting the signature of Father Fullana, the only eminence in linguistics, grammar and philology in Valencia and who could attach any value to those 8 pages of which 3 were reserved for signatures.

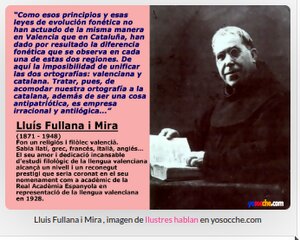

The first obvious question is: why did Fullana sign that document? Fullana evidently didn't want to sign it. First, because he knew it would mean denying his own rigorous and scientific work (Fullana always explained the rules by which he abided), his own standards (1914: Normes Ortográfiques; 1915: Gramática Elemental de la Lengua Valenciana; 1922: Compèndi de la Gramática Valenciana; 1932: Ortografía Valenciana), standards that corresponded to the educated Valencian of the 20th century, according to the various laws of linguistics, such as evolutionary phonetics, which he had applied.

By that time, he had already defended the originality and independence of Valencianp from Catalan before the Royal Spanish Academy[3] (11/11/1928), and the academic Josep Alemany Bolufer, also Valenciano, had replied, reinforcing this statement by also providing more bibliographical references supported by the works of the then director of the RAE, Ramón Menéndez Pidal. Secondly, because he knew what those supposed Valencianists (pro-Catalanists) were up to, although he had already said in an article that it seemed absurd to him. And thirdly, because he knew that it was a serious detriment to the Valencian language to divert it from its natural evolution and allow it to be diluted in Catalan. In March 1919, he had declared again: „the impossibility of unifying the two orthographies: Valencian and Catalan.

Trying to adapt our orthography to Catalan, besides being unpatriotic, is an irrational and illogical enterprise“[4]. Of course, Fullana never went to Castellón, among other reasons because he lived in Madrid, dedicated to his work as an academic of the RAE (consequently, he could not have been the first signatory as the pan-Catalanists claim). They had to go there three times to beg him to sign [5] and Fullana finally agreed due to the alleged pressure from his hierarchical superiors, a fact that had already occurred in 1919, leaving written proof of it in his article of April 17, 1919 in the newspaper Las Provincias. He had written „after censure by our superiors“, who had forced him to stop correcting the Catalanizing grammar of the young Bernat Ortín Benedito; something he had been doing for several weeks through various articles[6] in that same newspaper. From then on, Fullana stopped criticizing that grammar, and no more of his articles appeared. And as if that were not enough, he was also unable to publish his work: Linguistic Differences between Valenciano and Catalan, something he had already made a great deal of progress in, based on his lectures given in Barcelona in 1915[7] (invited at the time by the Institute of Catalan Studies and the Catalan Academy of Language, who tried but failed to convince him). There, in person, he had explained and reasoned these differences between Valenciano and Catalan. Why did Fullana give in in the end? Because he was a priest and had taken the three mandatory vows: poverty, chastity, and obedience.

Therefore, Fullana owed obedience to his superiors, and of course we know that within the Church, Catalanism was strongly rooted (the Monastery of Montserrat in particular and the Catalan Jesuits). So, faced with the dilemma of having to sign, Fullana did so by adding a note that attempted to minimize the scope of what was written there, introducing the keyword „Provisional“ and saying: „Given the provisional nature of the previous Bases, we have no problem signing them“. Incidentally, all those who praise the „Bases of Castellón“ never mention this warning from Fullana, nor what Lo Rat Penat (the leading entity of Valencianism) wrote, which was even more precise in expressing its criticisms.

After the silence of the Franco regime, during which the pan-Catalanists (Manuel Sanchis Guarner, Joan Fuster, and others) continued the always subdued and silent work of Catalanization at the University of Valencia, the Socialist Party (PSOE) distinguished itself in the „Battle of Valencia“ by defending the pan-Catalanist theses, hence the War of Symbols (1977-1982). Even before the Transition, the University of Valencia can be considered a bastion of pan-Catalanist theses, thanks to the painstaking work of undermining and lies it carried out. When the PSOE came to power in the Generalitat in 1983, that party enshrined the „Bases of Castellón“ through the Law on the Use and Teaching of Valenciano (Law 04/1983 of November 23). It was once again a political decision, as was the subsequent ruling of the Valencian Council of Culture in July 1998. This was due to the fact that in 1995 the Valencian Generalitat had passed into the hands of the Popular Party, but in 1996 the PP, winner of the general elections, without an absolute majority, found itself needing the votes of another party for José María Aznar López to be invested as Prime Minister. He was 20 seats short of an absolute majority (176), and the Catalanist party Convergència i Unió (Convergència i Unió) was willing to support the PP in exchange for more powers for Catalonia and, above all, on the unrenounceable condition of ceding to Catalonia the linguistic competence of the Valencian Community. The pact was forged, and Jordi Pujol obtained the linguistic competence that had eluded him during the „Battle of Valencia“ Catalanists accepted the designation of the language as Valencian in exchange for recognizing its Catalan nature (just as the Catalan language is called Valencian in Valencia), and the unity of the language was accepted, always understood as „Catalan unity“. This implied that Valencian literature would become part of Catalan literature.

And as if that weren't enough, the terms for the creation of the Valencian Academy of Language, not the Academy of the Valencian Language, were agreed upon precisely to prevent the expression „Valencian language“. On April 8, the pact was sealed, dubbed the „Reus Pact“, as it was held in that town; and shortly after, on May 4, Aznar was able to be sworn in as Prime Minister thanks to the „Majestic“ Pact, which embodied the entirety of the investiture agreement. Everything was decided, and consequently, what would follow would be merely a theatrical performance so as not to appear to be violating the rights of the Valencian people. On September 17, 1997, the Corts (Spanish Parliament) asked the Valencian Council of Culture (CVC) to issue an opinion on the linguistic status of Valenciano supposedly taking into account scientific and historical criteria. Once again, the political motivations and decisions that would underpin the final opinion were studiously avoided. The protests of Josep Boronat Gisbert, Xavier Casp i Verger, and Leopoldo Peñarroja Torrejón, who took part in the defense of the originality of Valenciano as opposed to Catalan, were of little avail. The conclusions of the report were released on July 13, 1998, adhering point by point to what had been agreed at the political level and, consequently, lying about the nature of the „Bases of Castellón“ This has evidently allowed the process of Catalanization of Valencian to be consolidated, and this is what the Valencian Academy of Language (AVL) has been doing ever since, guaranteeing and providing official cover for this institutional sleight of hand (or con job). This perversion of language allows pan-Catalanists to claim to defend Valenciano in schools, when in reality they are defending Catalan, because what is taught is Catalan and not the true Valencian language governed by the Norms of El Puig (the updated Norms of Fullana) and not those of Castellón. It can now be stated that everything the left defends as „Valenciano“ (language, literature, fallas, culture in both its learned and popular aspects) is being transferred to Catalan heritage; which constitutes a genuine plunder. Sometimes these left-wing representatives (now all pan-Catalanists) make this transfer openly, shamelessly declaring that they speak Catalan; other times they limit themselves to saying only that they speak Valenciano. But if you, the reader, want proof that in the mind of this political representative, Valenciano is Catalan, you need only declare that Valenciano is not Catalan and never has been. Then you, the reader, will be able to experience firsthand how you are labeled a „fascist“ or, at best, a „blavero“ (flapper); which for pan-Catalanists is the same thing. But the person offending you will only demonstrate their arrogant ignorance or their arrogant hypocrisy.

by Por Josefa Villanueva Espinosa.

Doctorada en Filología Hispánica por la Universidad de Paris-Nanterre. Su tesis: Le nationalisme valencien du XXIe siècle. Cent ans de pancatalanisme 1906-2006 está en parte publicada a través del libro El nacionalismo valenciano. El porqué y el cómo de las Bases de Castellón, (Editorial L´Oronella, Valencia, 2019).

| | | | Hier klicken, um newsletter zu bestellen oder zu stornieren |

Ein Buch das u.a. enthüllt:

Sprachdiktat in Katalonien und Valencia

Was sagen die Verfassungen?

Migration als Ursache?

Indoktrination und Korruption

Schnelleinführung in den Katalonienkonflikt

Aus einem Artikel auf kenfm.de im Okober 2019 zum Artikel

Aus einem Artikel auf kenfm.de im Okober 2019 zum Artikel Sprachen in Spanien

Spanisch, Baskisch, Katalan, Mallorquin, Valenciano etc.

Mythen und Täuschungen des katalanischen Nationalismus

Hier finden Sie die Übersetzung

Die Strategie der Rekatalanisierung

1980 veröffentlichte ?El Periodico? ein geheimes Strategiepapier der katalanischen Regierung. Es zeigt in erschreckender Weise die tatsächliche Geisteswelt der separatistischen Führer auf

1980 veröffentlichte ?El Periodico? ein geheimes Strategiepapier der katalanischen Regierung. Es zeigt in erschreckender Weise die tatsächliche Geisteswelt der separatistischen Führer aufJetzt liegt es in deutscher Übersetzung vor

Pankatalanismus

Kataloniens imperialer Anspruch

Die katalanische Regierung exportiert den Konflikt, in dem sie in den anderen Gemeinschaften, in den Katalanen leben, alle Bestrebungen zur Zerstörung Spaniens unterstützt.

Die katalanische Regierung exportiert den Konflikt, in dem sie in den anderen Gemeinschaften, in den Katalanen leben, alle Bestrebungen zur Zerstörung Spaniens unterstützt. Ein wichtiges Instrument ist dabei die Errichtung einer Sprachdiktatur, die sich nicht scheut, die gleichen Mittel wie Franco einzusetzen.

Separatistische Indoktrination

zur Untersuchung^

Demokratie und Sprachzwang

Ein Aufsatz in 6 Teilen über die potentiell gewaltauslösende Wirkung von Sprachzwang mit Beiträgen aus Südafrika, Katalonien, Ukraine und Frankreich.

zum 1. Teil

Die Papierversion ist jetzt im Verkauf

Die Papierversion ist jetzt im Verkauf