Not a free choice

Should we protect languages?

October 24, 2024

Between 26 November and 4 December, a „referendum“ is to be held in the schools and universities of the Comunidad Valenciana on the entry into force of the „Law on Educational Freedom“, which puts an end to the multilingualism model of the previous Botànic government

As good as it is to get an overview of the will of those affected or the parents, the terms „educational freedom“ and „multilingualism“ used in this survey are deceptive, as is the assumed possibility that the participants or parents can really decide on the languages of instruction with this survey.

As the Información from Alicante reports, despite the referendum, „the Valenciano must remain an educational priority“ and concludes by asking „Should the preference of the family take precedence in the organisation of the language, or is it necessary to pursue a firm policy to protect the Valenciano?“ A deceptive choice with questionable arguments.

Valenciano remains with at least 25%

The legal framework remains the so-called law of multilingualism, which provides for a minimum rate of 25% for Valenciano, as reported by VN Valencia Noticias.

That is why the referendum only serves to „obtain the opinion of families“ 1. They will not have a say, as promised before the election by the parties now in power.

Nevertheless, this referendum offers opportunities to influence schools and communities. We should utilise them.

Who or what needs protection?

The newspaper article describes the regulation as an attempt to „protect and promote the use of Valenciano, a minority language that ... needs support measures to ensure its continuity over generations.“ Why? How many generations should we dictate which language they should use? Latin is a dead language today. Who knows in how many generations Spanish or English will be the same?

We must always remember this. Only humans have rights. Tools do not. Language is a tool, albeit a very special one, which can be used to express and trigger feelings, just like music. What's more, language is constantly changing. Even if it seems useful to find rules for languages (e.g. grammar etc.), they cannot be protected.

It is different with speakers of a language. Their rights can and must be protected. For all Spaniards, this includes being able to express themselves to the Spanish state in their mother tongue and for the state to deal with them in the language of their choice. Pupils should be guaranteed lessons in their mother tongue because it is easier to learn in it. Taxpayers' money should also be used to promote the traditions and cultures of all Spanish minorities - in peaceful coexistence.

Language requirement in Spain, Belgium and Switzerland

Article 3 of the Spanish constitution states: „Castellano is the official Spanish language of the state. All Spaniards have the duty to speak [Correction - see below] it and the right to use it.“ (Castellano is a useful term within Spain for the language known and used worldwide as Spanish).

Castellano as a duty sounds very sensible, but is it also democratic?

A look at Belgium2 (trilingual) and Switzerland (quadrilingual) reveals completely different possibilities for a liberal approach. In both countries, there is no obligation to speak one of the official languages. There are various degrees of possibilities to use a state-funded interpreter when I am in a part of the country where another language is spoken. This is particularly important in court, where this regulation is intended to ensure a fair trial with 100% coverage.

Whoever imposes a language obligation on another risks the resentment of those coerced to do so. Franco achieved this with his language dictatorship for many Spanish minorities. Catalan and Valencian separatists3 are doing the same today with their exclusion of Spanish and this often leads to a childish emotional defiance.

But it's understandable. I also shout angrily „bloody hammer“ when I hit my thumb instead of the nail. That's not sensible. You should always look for blame and understanding in yourself first. That means people, not tools.

Language imposition protects nothing and no one. In the worst case, it leads to confrontation between users and doesn't solve a single problem.

Correction

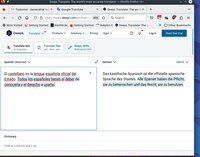

Of course, I also use translation programmes. Using „copy and paste“ saves a lot of time and avoids some spelling mistakes. But translation programmes are not error-free, as you can see from the picture to the left. I had copied the text from the constitution and copied the German result into my text without checking it.

But the translation into German was wrong

I am writing my articles in my mother tongue and then translate it into English. This time the already wrong translation into German was now translated into English, again wrong. My big error must have been a kind of thinking „such an easy text should not be a problem for the programme DeepL.“ It was.

The correct translation of the Constitution at this point is: „All Spaniards have the duty to know it“. I would like to thank Antonio J. for drawing my attention to this error. 27 October 2024

Footnotes

1 recoger la opinión de las familias

2 Before Spain I lived in Belgium and in this paragraph I am referring to my memories and the information I got from chatgpt.com.

3 The Valencian president also sees the strict Valencian language dictators as separatists, as El país reported on 25/09/24. „50 diputados recurren al Constitucional la ley valenciana de Educación y Mazón los califica de 'separatistas'“

| | | | Click here to subscribe or cancel your subscription |

Myths and deceptions of Catalan nationalism

Here you'll find the translation

Languages in Spain

Spanish, Basque, Catalan, Mallorquin, Valenciano etc.

The strategy of recatalanization

1980 the Spanish journal "El Periodico" published a secret document about the strategy of the Catalan government. It shows in a frightening way the actual spiritual world of the separatist leaders.

1980 the Spanish journal "El Periodico" published a secret document about the strategy of the Catalan government. It shows in a frightening way the actual spiritual world of the separatist leaders.Now it is available in english translation.

Pancatalanism

the separatist's imperial claim

The Catalan government exports the conflict into communities with Catalan population, supporting all efforts of the separatists including financial means to destroy Spain.

The Catalan government exports the conflict into communities with Catalan population, supporting all efforts of the separatists including financial means to destroy Spain. An important tool is the establishment of a language dictatorship that is not afraid to use the same means as Franco.

Separatist indoctrination

Click here to read the study

Language imposition and democracy

An essay in 6 parts on the potentially violent effect of language imposition containing contributions from South Africa, Catalonia, Ukraine and France.

go to part 1 SticSti

Publications

The title says: "Catalonia, a conflict is exported. Insights of a migrant"

The title says: "Catalonia, a conflict is exported. Insights of a migrant"Sorry, up to now, this book is only available in German. However, drop us a line, if you are interested to learn more Contact.